Long overdue, my coverage of the excellent conference, Vector: Game + Art Convergence, that took place at various locations in Toronto from February 21st to 24th 2013.

* * *

It was on the very last day of the Vector: Game + Art Convergence conference in Toronto, ON, during the final panel, that a member of the audience asked the four speakers and moderators what they thought about the equation of games with art. The panel’s topic was “The Politics of Appropriation in Game Art,” and was moderated by Felan Parker, with participants Chris Burke and Tamara Yadao (also members of foci+loci, who explore the space and time within video games through experimental musical and visual performances), Martin Zeilinger, and Alex Myers. The panel itself was engaging, as all members on it straddle the line between academics and experimental artists in a variety of ways, but there was something about this question that took everyone aback. After answering, in incredible details, many fine, detail-oriented inquiries about everything from the legal ramifications of appropriating game material from AAA releases to make art to the nitty-gritty of each participants style and interests, the question of “are games art?” was still a challenge.

After batting the question around for a moment, the panelists settled on the idea that to ask if games are art is not a particularly useful questions, because it assumes the answer will ether be yes or no. Tamara Yadao likened it to asking if air was breathable. “The answer is yes – some of it.” It’s not that “are games art?” is a stupid question, but a multiple question, one that must be posited constantly in every context that games appear. It is a question with no absolute answer, but a whole glorious, glitchy ocean of grey area.

In fact, it is this question, and it’s essentially unanswerable nature, that the entire Vector Game + Art Convergence was based around. The Conference, which took place from February 21st to 24th at various venues throughout the city (including the Bento Miso co-working space, InterAccess and Propeller fine art galleries, and Videofag cinema and performance space), didn’t attempt to answer this question simply or bluntly, but rather presented a variety of ways in which the confluence of games and art could possibly take place.

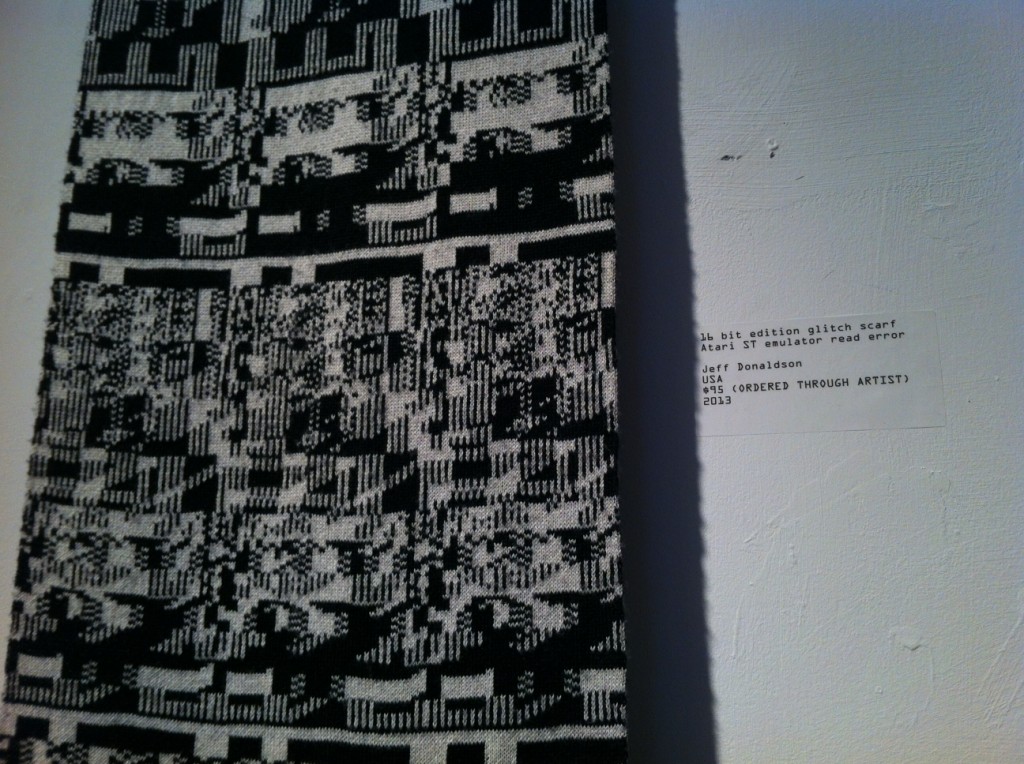

There were many ways in which the conference achieved this goal. All of the panels discussed games and gaming culture in a way that presented games as cultural artifacts warranting serious critique. The panelists themselves were all specialists, whether they were artists or not, who treated games as art, either consistently or occasionally, in their own work. Games were featured art games as installations, many of them presented games in gallery spaces, and therefore were contextualized as playable works of art. There were also many examples of ways in which games could be manipulated into becoming art or hijacked to be art, especially during the evening performances by artists like Toca Loca (who performed their Halo Ballet), Foci + Loci (who created an immersive sound space using Little Big Planet) Angela Washko and others. The exhibitions also featured art that was inspired by or somehow created within games, everything from the stunning piece of textile art “The Glitch Scarf” to a book of war stories all lifted from experiences in first person shooters. There were also several screenings throughout the festivals of art films based on games and films that treated games as art, such as Stranger Comes To Town” Identity and the Avatar, and the Suerpcade! event, which featured a collection of commercials, shorts and other video/gaming ephemera presented as art.

Perhaps most successful of all was the way that Vector presented participants with the opportunity not only to explore intellectually the ways in which games could be art, but also to experience games as art my playing them, and making them. All of the exhibited games throughout the festival were playable, implicating the viewer and making them an active participant in the process. Also, there were a number of workshops and jams that allowed participants to make their own (potentially art) games as well or make their own art out of games. Chip.jam (led by Jeff Alynak, Roger Bongers and Pete O’hearn) taught participants to use game technologies to make music, noise art and sound; glitch-jam allowed participants to create glitch-based art via video game consoles; and micro-Twine.jam, led by Damian Sommer, led participants through the process of making their own interactive narrative using the Twine engine. The Twine jam workshop was particularly exciting for me, as it was an easy and hands-on way to learn some of the best and most basic tools within the software, while simultaneously being presented with a structured opportunity to write a game. For writers who are interested in learning to write for games, Twine is an incredibly powerful tool, and showing how it could be used within the context of exploring games as art was extremely useful.

Vector: Game + Art Convergence is a gaming conference full of promise. In a city like Toronto, bursting at the seams with indie developers, gaming groups, start-ups and game artists, having a conference like this specifically devoted to exploring the way games can be art is both valuable and needed. After an incredibly successful inaugural conference brimming with intelligently-selected and fascinating programming, it will be very interesting to see how Vector continues to evolve in the coming years.